Blog Article List††††††††††† Home††††††††††††††††† Contact Me

|

Stokes: DNA, Tilley, Hill, estate July 20, 2020 The 1836 Estate of Edmund

Tilley of Stokes Co, NC Two weeks ago I didnít know I was a

descendant of Edmund Tilley.† Four

years ago I didnít even know I was a descendant of his granddaughter Letitia

Hill Wood.† But thanks to DNA results,

I was able to fill in these gaps in my family tree. I write a lot about DNA, but I donít

want to be misleading.† Itís not a

situation where you take a DNA test and all of a sudden you have a list of

all your ancestors.† That would be

nice, but itís not that easy.† If you

think of it as a jigsaw puzzle, taking a DNA test is like dumping the pieces

onto the table.† Itís only the first

step.† Putting the puzzle together takes

time and patience, but eventually the image will start to appear.† It takes a lot of research to fully

understand the events from long ago, and itís only through sharing and

comparing results Ė DNA and otherwise Ė that weíre able to solve these mysteries.† Weíre each able to contribute different

pieces of the puzzle.

Iíve recently been studying my list of

DNA cousins, and Iíve noticed that I have clusters of matches who have Stokes

County ancestors in the early 1800s.†

More specifically, several of them descend from the Tilley, Wood,

Lawson, and Collins families.† Four

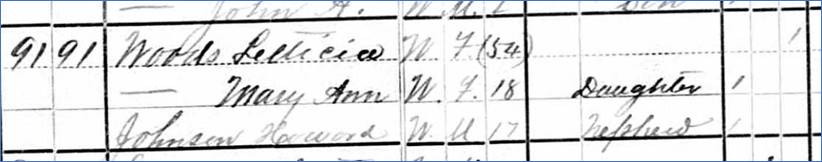

years ago I found out that I had a 4X-great grandmother named Letitia Hill

who was born in 1825 in Stokes Co, and she married Adam Wood there in 1843. One of the clues about my Letitia Hill Wood

is that she had a nephew Howard Johnson Hill who was born about 1862.† That means Howardís father was likely

Letitiaís brother.† Howard was living

with Letitia in the 1880 Grayson Co, VA, census.

If I could find out who Howardís father

and grandfather were, then Iíd be able to fill out my family tree one more

generation.† I found a tree online that

showed Howardís father as Phillip Hill who died in 1862.† Phillip was the son of Frederick Hill and

Elizabeth Tilley; and he was the grandson of Edmund Tilley.† If Phillip and Letitia were brother and

sister, then Edmund Tilley is my newfound ancestor. But I donít want to base this new

branch of my tree on only one undocumented family tree I found online.† I need at least a little proof.† DNA provides some initial evidence because

I have more than a few groups of DNA matches who also descend from Edmund

Tilley of Stokes Co.† I also noticed

that Frederick Hill and Elizabeth Tilley Ė the suggested parents of my

Letitita Hill Ė had two other daughters who each named a daughter

Letitia.† That is, if my theory is

correct, the girls were named after their aunt Letitia who was my ancestor. I also looked at all the other Hill

households living near Letitia and her husband.† After a process of elimination, only

Frederick Hill was a possibility to be her father.† Of course, another possibility is that her

father lived farther away or that he had died years earlier.† Still, the man who I presumed to be her

father was still a candidate.† While these

clues arenít definitive proof, when taken as a whole, the circumstantial

evidence is enough for me to add these new names to my family tree until I

can prove the theory wrong.† And thatís

where Edmund Tilley comes in.

Edmund Tilley was born in 1740, maybe

in the eastern part of Virginia.† He

moved to the Stokes Co area, and lived near the NC/VA border until his death

in 1835.† He was in his 90s, and he was

feeble and unable to tend to his daily affairs on his own.† He had lived a long life, and he left seven

children to mourn his death. The estate file for Edmund Tilley shows

that his children disagreed about the details of his Last Will and Testament.† Edmundís son David was appointed the executor,

and he began fullfilling those duties within a month of his fatherís

death.† However, when the will was

produced in court in March 1836, all of the other children filed a caviat

claiming that the will was fraudulent and that David secretly had his father

sign it even though he ďhad become so weak and impaired in understanding that

he was incapable of transcribing the most ordinary concerns of lifeĒ. Here is the text of the will dated

10/7/1829. In the name of God Amen. I, Edmund Tilly Senr of the County of Stokes,

being mindful of my mortality but believing in a resurrection to eternal

life, do this seventh day of October in the year of our Lord Eighteen Hundred

and Twenty nine make and publish this my last will and testament in manner

following. First, I bequeath my body after my decease to its natural Earth to

be decently intered. Secondly, I give and bequeath to my son David Tilly my Negro Martin to

him and his assigns forever. Thirdly, I give and bequeath unto my son David Tilly my Negro girl

Melinda and her increase by paying Two hundred and fifty dollars in three

years after my decease. Fourth, I will that my negro woman Becky and my Negro boy Jim be

sold after my decease and the money equally divided among my children. Fifth, I will that all of my lands be sold and the money equally

divided among my children. Sixth, I will that all my household property be sold and equally

divided among all my children and I do hereby constitute David Tilly and

Matthew R. Moore executors of this my last will and testament. In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and

seal the day and year first above written, signed, sealed, published, and

declared by the said Edmund Tilly Senr as his last will and testament in our

presence who at his request in his presence and in the presence of each other

have subscribed our names as witnesses thereto. Unfortunately, Edmund Tilley owned

slaves and their disposition was handled like any other property that he owned

at the time of his death.† Son David

received his slave Martin, and this is the only instance where David received

more than any of his six siblings.†

While David was also to receive slave Melinda, he would need to pay

$250 back to the estate.† Everything

else Ė two more slaves, land, and household property Ė would be sold, and the

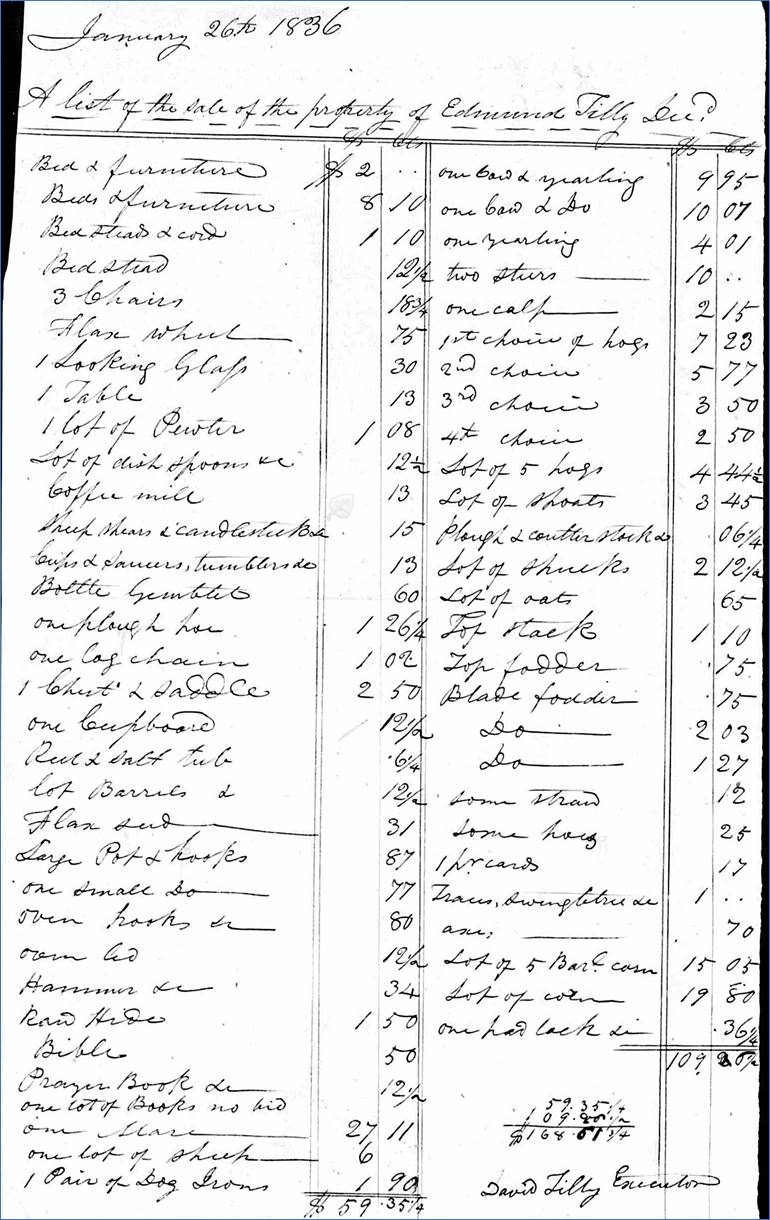

money would be divided equally among all the children. This is a list of the household

property sold on January 26, 1836.

I still donít know why the other six

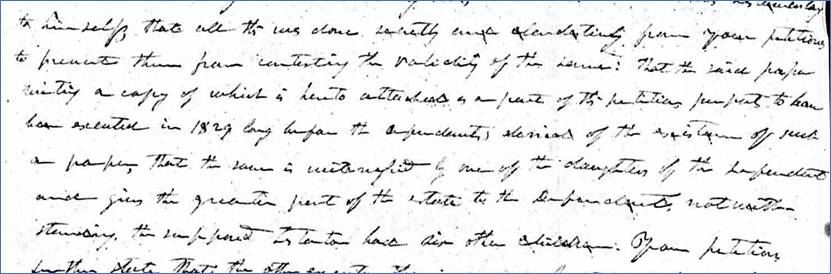

were so unhappy with the instructions in the will, but they were.† Among the documents is a lengthy claim that

David had secretly manipulated their father and that he had previously denied

the existence of a will when his sister Elizabeth had asked him about it.† They wrote, ďthat all this was done secretly and clandestinely

from your petitioners to prevent them from contesting the validity of the

same.† That the said paper writing, a

copy of which is hereto attached as a part of the petition, purport to have

been executed in 1829 long before the defendant [David] denied the existence

of such a paper.† That the same is witnessed

by one of the daughters of the defendant [Phebe] and gives the greater part

of the estate to the defendant, not withstanding the supposed testator had

six other children. †

Yes, itís difficult to read. It seems that the biggest complaint

from the other siblings is that they werenít told about the existence of a

will.† It does seem like David intentionally

kept it a secret.† He denied knowing

there was a will to his brother Edmund Jr and to his sister Elizabeth.† And Davidís own daughter Phebe served as

one of the two witnesses at the age of just 18. Maybe there was a reason for his

behavior.† Maybe dad Edmund Sr knew

that all the children would just argue over his estate, so he told his

trusted son David to keep it quiet. In the end, the case went to three

courts in both Stokes and Rockingham counties.† The Superior Court ruled in 1837 that the will

should be recorded and accepted as written.†

By 1842 the estate had been settled with each of the seven children

getting about the same amount with the exception of David who received one of

the slaves.† The only discrepancies in

the amount each child received was due to court costs and other outstanding

bills. The estate file is available online,

and it consists of 35 pages.† I transcribed

it, and itís available here.† Itís

also available on the Records

page.† Along with the drama

surrounding the case, the file provides genealogy information that might not

be available elsewhere.† It lists Edmundís

children, provides his death date, and gives a description of his

health.† It gives a small amount of

information about where they lived and who some of the children married.† If youíre lucky enough to find an estate

file for an ancestor, it can be a helpful source of information.

Comments?† jason@webjmd.com |